|

Early Autoharp Chord and Note Numbers

This overly-detailed article is written to explain the weird labeling system on early 3, 4, and 5-chord autoharps, especially why they label both A and Bb as note number 6.

When German-American Charles F. Zimmerman patented an autoharp design, he began producing autoharps based in part on earlier German designs that involved pushing buttons to dampen strings. Though his patent shows an instrument shaped like a pregnant vase, the autoharps he built to sell used an asymetrical trapezoid design that reflected the earlier German designs and set the standard for almost all autoharps built since. When German-American Charles F. Zimmerman patented an autoharp design, he began producing autoharps based in part on earlier German designs that involved pushing buttons to dampen strings. Though his patent shows an instrument shaped like a pregnant vase, the autoharps he built to sell used an asymetrical trapezoid design that reflected the earlier German designs and set the standard for almost all autoharps built since.

Zimmerman was hopeful that the autoharp could bring music into the lives of many people who would never have formal music training. So he designed and promoted a new way of reading and playing music, which used numbers and symbols instead of note and chord names.

- Notes for the C major scale were shown as numbers in black: C=1, D=2, E=3, F=4, G=5, A=6, B=7. If you're a musician, you're used to using such numbers, with one caveat: C was ALWAYS #1, even if the song was in F.

- Flats were not shown; all accidentals were shown as sharps. So what most people would call a Bb was considered an A#.

- Sharps were shown by printing the note numbers in a dotted font.

- Chord names were not shown. Instead a C chord was always indicated by a 1, an F chord was always indicated by a 4, and so on - even if the song was in the key of F.

- The numbers for major chords had a dot underneath them. So an F chord would be labeled by a 4 with a dot underneath it.

- The numbers for major chords names with a flatted seventh had a line underneath them. So a G7 chord would be labeled by a 5 with a line underneath it.

The numbering system applied not only to Zimmerman's printed scores, but to the labels on the chord bars of his autoharps as well.

Numbering Chords and Notes on a 3-Chord Autoharp

Zimmerman's earliest autoharps were not chromatic, like today's autoharps. The strings were tuned to the notes of the C Scale, plus Bb, making them more or less diatonic. Imagine a piano on which you removed all of the black keys except for the Bb key, and you'll have some idea.

Because the early autoharps were relatively simple, the numbering system was relatively easy for untrained musicians to understand, especially on Zimmerman's early 3-chord autoharps. These were suited for playing three-chord songs in C. Because the early autoharps were relatively simple, the numbering system was relatively easy for untrained musicians to understand, especially on Zimmerman's early 3-chord autoharps. These were suited for playing three-chord songs in C.

- The C chord bar is indicated by a 1 with a dot underneath it. The label also shows that the chord contains the 1st, 3rd, and 5th note of the C scale. Easy enough

- The label for the F chord bar shows a 4 with a dot underneath it. The label also shows which notes of the (unlabeled) C scale are used for that chord - the 4th (F), the 6th (A), and the 1st (C).

This can be confusing for people trained to think of all major chords as being 1/3/5, with the 1 representing the tonic of the chord. But if you think of a piano with the white keys numbered from 1 to 7, you'll "get" why an F chord could be labeled 4/6/1.

- The label for the G7 chord bar shows a 5 with a line underneath it. It also shows that the following notes of the C scale are used in that chord: the 5th (G), the 7th (B), the 2nd (D), and the 4th (F).

Why put the note numbers on the chord bars? Because it would make it easier for folks who knew Zimmerman's system to figure out which melody notes were embedded in each chord.

Numbering Chords and Notes on a 4-Chord Autoharp Numbering Chords and Notes on a 4-Chord Autoharp

For some reason, when Zimmerman expanded the number of buttons on the Model 2, he added a C7 chord, which includes what North Americans call a Bb note. If he'd added a Bb chord instead of a C7, he could have made the thing playable in the key of F, but he didn't. This model didn't last long, and there are few good photos of the ones that are left, but close examination shows that three of the chord buttons are the same as those on the 3-chord autoharp, though on some examples (not this one) they have shifted around.

But the fourth chord button (you have to trust us on this) is labeled 1 Seventh 1356. In Zimmer-speak, that's the C chord (1/3/5) with an added note. But the added note, which we would call Bb, is labeled as a 6. To make things more confusing the A natural note in the F chord ("4") is also labeled "6." On later autoharps, the "6" that represents Bb is shown in a different typeface than the "6" that represents A natural, but you can't really see that on this example.

However you can see that the note names under the individual strings go 12345667. The second 6 on that label is fainter than the other six. In fact, the numeral is dotted, not solid - it's just hard to tell in this photo.

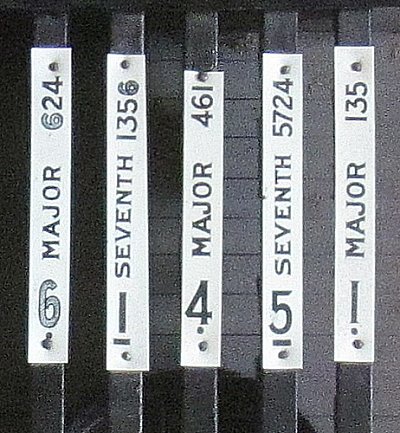

Numbering Chords and Notes on a 5-Chord Autoharp

You can't sing every song in the key of C, even if you add C7. So Zimmerman started making 5-chord autoharps, which turned out to be very popular. You can't sing every song in the key of C, even if you add C7. So Zimmerman started making 5-chord autoharps, which turned out to be very popular.

The chords on the 5-chord Zimmerman autoharp were G7, C, C7, F, and Bb. But even though you could now play 3-chord songs in F, Zimmerman didn't want to mess up his system by using chord names. In his music system, he wanted even the songs that were based in F to use the numbers he had assigned to notes in the C scale.

So Zimmerman continued to call Bb a "6," but putting it in a different typeface than the A (which we would call the 6th). The Bb chord bar is labeled with a hollow-looking 6 with a dot under it. That tells folks familiar with Zimmerman's system that the chord is a major chord that is half step up from a "natural" 6th chord.

The "tonic" note on the Bb chord is also indicated as a hollow-looking 6. If you look closely at the photo to the right, you'll see that the "4" chord has a solid black "6," which represents an A natural. But the "1 Seventh" chord (C7) has a hollow-looking 6. Confused? No need to be. Modern players of these vintage instruments just learn which chord bars play which chords and go on from there. Sooner or later, autoharp players learn to change chords by touch, not by sight, anysay.

By the way, I have seen blurry photographs of 5-chord autoharps that have a chord bar labeled "2" where the Bb chord bar would have been, but these are relatively rare, and I can't swear to what chord they actually played (perhaps D7, which would let you play three-chord songs in G).

Further Expansions

Soon after the 5-chord autoharp was marketed, the Zimmerman family's interest in the autoharp were sold to Afred Dolge, who continued to manufacture autoharps under the C.F. Zimmermnan name. Zimmerman's 5-chord version continued to be popular - so popular that it eventually was branded "The Favorite."

Not mentioned in this account are the "shifter" autoharps - instruments that could play more chords than they had buttons because you could push little push bars sideways to engage other pads. Very few of these have survived in playable condition - there are too many moving parts. But their labels are even more confusing than the labels shown above.

Dolge continued to add chord bars. But expanding Zimmerman's chord numbering system to other keys became more cumbersome as more chord bars were added. About 1895, Dolge began using chord names instead of numbers on his 7-button autoharps, though the numbering system was still used on 5-chord autoharps for decades.

After Dolge's autoharp business faltered, and it was picked up by the Phonoharp company, even more chord bars were added. Then Oscar Schmidt took over and never looked back, as 12-chord and then 15-chord autoharps became standard.

Surprisingly, Oscar Schmidt's 5-chord autoharps continued to use numbers - not chord names - until about 1952. So if you have a 5-chorder with numbers, not chord names on the bars, you have to look at other aspects, like whether the chord buttons are wood or bakelite, to truly date the things.

Several other short-lived brands used Zimmerman's numbering system as well, including the bizarre "Meloharp," which represented the Bb chord both as 6 with a line through it and as a 7 with a line through it. Ooops.

Conclusion Conclusion

How did I get involved in such a peculiar discussion? I was trying to show someone my early Autoharps and kept bumping up against the "two 6 notes on each scale" problem.

Ironically, my early 5-chorders - a Dolge-era "mini-harp" (the brown one) and a Phonoharp-era "Favorite" - are both in better shape than some of my early Oscar-Schmidt 12-chorders, which might be as much as 30 years newer. Perhaps because the newer models had enough strings to play the complete chromatic scales on the upper and mid octaves - the older models only had a diatonic C scale plus Bb (or A#) as it came to be labeled.

There's no compelling reason I couldn't replace the rusty strings on either of my 5-chorders and play them. There are cracks in the back, but not in the face, whereas two of my early Oscar Schmidt 12-chorders have cracked faces. 36 strings versus 23, and no significant improvement in bracing - go figure.

Back to the discussion of 5-chorders, sort of. The "standard" 36- and 35-string autoharps that ruled from the early 1900s on were/are cumbersome, especially for beginners and people with short arms.

Sometime in the 1970s, Oscar Schmidt introduced a 6-chord compact harp, obviously intended for children. The chords were G, D7, C, C7, F, and Bb, which allowed you to play three-chord songs in C, F, and G. Not too bad, really. (OS also made a 10-button "Easy Chord" mini-harp, not shown here.) Sometime in the 1970s, Oscar Schmidt introduced a 6-chord compact harp, obviously intended for children. The chords were G, D7, C, C7, F, and Bb, which allowed you to play three-chord songs in C, F, and G. Not too bad, really. (OS also made a 10-button "Easy Chord" mini-harp, not shown here.)

To compete, Chromaharp introduced a 5-chord mini-harp, using the same chords as the old Zimmerman-labeled models - G7, C7, C, F, and Bb. I have two responses to this autoharp:

- Thank goodness they didn't go back to the numbering system, and

-

Why didn't they change the C7 to D7 and G7 to G? It has F#s on it (which you can't tell from the photo). Adding D7 would have given you the ability to play 3-chord songs in G, a popular Folk and Bluegrass key.

But the story of the Autoharp is largely a story of bold, sometimes ill-concieved experiments that either succeeded or failed spectacularly.  I count this among the failures. Though the OS 6-chorder hasn't been manufactured for over 40 years, it is still in high demand among autoharp afficianados. I count this among the failures. Though the OS 6-chorder hasn't been manufactured for over 40 years, it is still in high demand among autoharp afficianados.

The Chromaharp 5-chorder is not, to put it nicely.

Best of luck!

Whatever else you get out of our pages, I hope you enjoy your music and figure out how to make enjoyable music for those around you as well. Whatever else you get out of our pages, I hope you enjoy your music and figure out how to make enjoyable music for those around you as well.

And please stay in touch!

- Paul

http://CreekDontRise.com

http://SchoolOfTheRock.com

http://classictrainsongs.com

|

|