| Please Read: How to Help Our Site at No Cost to You - Some of our articles contain recommendations for products we like and vendors we personally trust. Some of those vendors may pay us a very small commission if you click on a link and buy their products. This costs you nothing at all and helps offset the costs of what we do. So if we point you to something you decide to buy later, please make certain you come back through our site and click on the link directly. Thanks. |

| This Site is a Cookie-Free Zone - Except for discussion forums that you have to expressly register for, none of our pages use cookies of any kind. Some of the vendors we link to do, but that won't affect you unless you click on a link to their pages. Your continued use of this page indicates that you agree to our policy. For details, click here. |

What Was the Folk Revival?

Why do I often use the term "Folk Revival" instead of "Folk"? First of all, there is a difference between Folk music and Folk Revival music. To put it simply (and at the risk of offending many people), Folk music is - technically - the unexamined and orally-transmitted musical heritage of a culture, while Folk Revival music (which emerged and peaked in the mid-20th century) is a deliberate adoption and proliferation of traditional music and traditional music styles by people who mostly did not learn this music from their parents or grandparents.I often call myself a Folk singer because calling myself a "Folk Revival" singer would make no sense to most people, but I'm a product of the "Folk Revival" myself. As were Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, the Kingston Trio, and countless other Baby Boomers who are generally called "Folk singers" to this day.

Note: As I recount the background and history of the Folk Revival movement, I will be leaving out about thirty of my own favorite Folk, Folk Revival, and Folk Rock artists, including some I have been friends with over the years. I'm sure I will also be leaving out dozens of yours. Please understand that I am attempting to describe an overall chronology, and not a list of "shout-outs" to anybody's favorite artists of the eras described.

On the other hand, if you are on this page and feel you are misrepresented in any way, please feel free to use my contact page to let me know. Or if you have access to relevant historical facts that are not in my personal experience or that my research did not turn up. Even if I don't adjust this article, I am planning on some follow-up articles and your input may be helpful.

What is Folk? - This question has started countless, and - frankly - pointless arguments in various circles, and my definition will surely raise some hackles. But for the purposes of this article, I'll define Folk music as music that uses, and over the generations defines, the musical "language" typical of a culture. (For example, in North America, Folk songs are usually based on pentatonic, diatonic, or Blues scales and three- to five-chord harmonization). Folk music also circulates through a culture so long that:

- It becomes part of the cultural framework.

- Countless variations exist.

- Nobody remembers who wrote the song in the first place. Or else,

- In the case of, say, Stephen Foster songs, nobody cares who wrote the song in the first place.

So the Folk music of England is different from the Folk music of, say, Korea, but both are products of centuries of generations of oral tradition.

Musicologists who study Folk music are most interested in songs and traditions that have not been influenced by popular music on the radio. That's one reason we don't see people like Alan Lomax, John Jacob Niles, or Carl Sandburg going into isolated communities or work camps or prisons to record and transcribe traditional music any more. Today, everyone has been influence by the radio (or CDs or MP3s or MTV or some such. A century ago, if you asked a coal miner or work gang member to sing five songs they learned as children, at least two of those songs would likely be Folk songs by the above definition. Today, all five songs are likely to be "pop" songs. Even if they're outdated by today's standards, they're still not Folk songs per se.

What is Folk Revival? - While musicologists like Alan Lomax and John Jacob Niles were bringing 100% traditional Folk songs to light, musicians from every background were learning and playing them. Some started writing songs in the same styles, and some of those songs "got away" from their authors and became Folk songs in the traditional sense, as well. Slowly, very slowly, the traditional music of America's poorer classes began to influence the music industry, which had originally focused on families rich enough to own pianos and to learn how to play them. By the mid-1950s, the influence was tangible, but we're going to dig a little deeper than that.

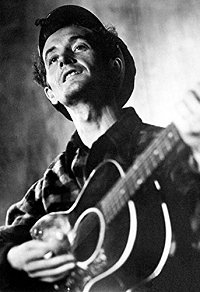

Pioneers of the Folk Revival - It's impossible to describe the Folk Revival without mentioning the influence of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, two people steeped in the Folk tradition, who helped popularize traditional songs and sounds to multitudes who would not otherwise have been exposed to them.

Woody Guthrie grew up in a series of impoverished environments; then during the Great Depression made his way across the country communing and commiserating with other disenfranchised, marginalized, or downtrodden people. When he wrote songs, he used the instruments, chord progressions, song structures, and even, sometimes, the melodies of the traditional music he had grown up with or learned on the road. He was also sensitive to the injustice he saw in the world around him, and many of his songs reflected that, sometimes humorously and sometimes not.

Woody Guthrie grew up in a series of impoverished environments; then during the Great Depression made his way across the country communing and commiserating with other disenfranchised, marginalized, or downtrodden people. When he wrote songs, he used the instruments, chord progressions, song structures, and even, sometimes, the melodies of the traditional music he had grown up with or learned on the road. He was also sensitive to the injustice he saw in the world around him, and many of his songs reflected that, sometimes humorously and sometimes not.

Of course, Woody is best known for authoring "This Land is Your Land," which sounds like a patriotic anthem if you don't sing all the verses. But even that song, in its original version, includes a dig at wealthy landowners who let huge tracts of land stand idle, while hundreds of thousands of experienced farmers, driven west by the dust bowl and mortgage foreclosures, were living on the road chasing down one temporary harvesting job after another.

Pete Seeger grew up in a music-loving family that appreciated traditional music, though he was exposed to many other

styles. Like Alan Lomax and other musicologists, he felt there was intrinsic value in the music of "the common people." Like Woody, he was concerned about injustice and cultural divides that kept downtrodden people under the thumb of the rich. But Pete was driven even more by a Humanistic or Jeffersonian sense that "the common people," those who were uncelebrated, who were often "shouldered aside" by the entitled classes, had intrinsic value and values that deserved to be recognized by North American culture as a whole.

Pete Seeger grew up in a music-loving family that appreciated traditional music, though he was exposed to many other

styles. Like Alan Lomax and other musicologists, he felt there was intrinsic value in the music of "the common people." Like Woody, he was concerned about injustice and cultural divides that kept downtrodden people under the thumb of the rich. But Pete was driven even more by a Humanistic or Jeffersonian sense that "the common people," those who were uncelebrated, who were often "shouldered aside" by the entitled classes, had intrinsic value and values that deserved to be recognized by North American culture as a whole.

In their early years, Pete and Woody often shared the same platform at union meetings, or socialist outreaches. For a time, they both belonged to a loose affiliation of "fellow traveler" musicians called the Almanac Singers. Though their careers eventually went in different directions, they always respected and supported each other, and Pete sang many of Woody's songs throughout his life.

When Pete formed The Weavers with Lee Hays, Fred Hillerman, and Ronnie Gilbert, Woody said that the group was like the Almanac Singers except they actually rehearsed.

As Pete traveled and wrote and sang, he stayed "grounded" by maintaining an acquaintance with musicologist Alan Lomax. But even more important, he sought out countless other musicians who, like Woody, had grown up and were still steeped in the traditional music of their ancestors. The list of people whom Pete brought into his "circle" would take up the rest of this article, but the point is that Pete was key to "Folk music" being seen not only as a cultural expression, but as a growing movement.

Early Incursions Into the Music Industry

At the same time that Pete, Woody, and others were traveling the country stirring up trouble (as the McCarthy-era witch hunters eventually claimed), a few Folk and Folk-influenced songs were finding their way to mainstream radio. "Casey Jones," whose author never received credit for the song in his lifetime, showed up in a number of early recordings. Vernon Dalhart's 1924 recording of "The Wreck of the Old 97" sold millions of copies.

sold millions of copies.

In 1927, the Carter family made their first recordings. By 1930, they had sold over 300,000 records. Although their biggest concentrations of fans were in Appalachia and the deep South, their records found their way into many northern record stores and eventually influenced Baby Boomers hungry for authentic sounds and songs.

In the 1940s and 1950s, other performers with Folk backgrounds or leanings received at least some attention from the industry, including Josh White, Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Hudy Ledbetter, Big Bill Broonzy, Oscar Brand, and Cisco Houston. Many of those recordings also found their way "up north."

Folk Goes Mainstream

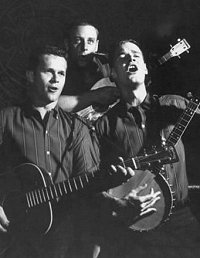

In 1950, the Weavers began having radio hits with songs like Hudy Ledbetter's "Irene Goodnight." Record companies began looking for other musicians with traditional leanings. Unfortunately, McCarthy-era blacklisting soon started keeping the Weavers' recordings off the radio. But by then, countless younger groups, often formed by Baby Boomers, had begun to take their place, not only in the clubs and coffeehouses, but also on college campuses, as well as college and independent radio stations. Like many of today's "indie record" movement, these artists survived by selling self-produced records and traveling long distances between badly paying gigs, but they did it for the love of it. As the music gradually found its way to commerial record companies, a handful of folks who started out with a guitar and a reliable station wagon did find their way to some measure of commercial success eventually. The most successful early Folk Revival band was the Kingston Trio. Their recording of "Tom Dooley" went gold in 1958. That

success (and continuous radio airplay) helped propell the careers of several contemporary groups and inspire the formation of many more.

The most successful early Folk Revival band was the Kingston Trio. Their recording of "Tom Dooley" went gold in 1958. That

success (and continuous radio airplay) helped propell the careers of several contemporary groups and inspire the formation of many more.

1958 was also notable for Jimmie Roger's "Kisses Sweeter than Wine," a Pete Seeger song that got significant radio airplay that year. Yes, Jimmie eventually found a home in the burgeoning Country and Western movement. But when that recording occurred, he was not quite pigeonholed as "Country" artist yet. Also, that recording gave Pete a little more attention, as well as a trickle of income when his own recordings couldn't get airplay.

Rock Just Died

Possibly contributing to the success of the Folk Revival movement was a sort of vacuum of "visceral," youth-oriented music on the radio. In 1958, when "Tom Dooley" hit the charts, Rock and Roll was on its way to becoming "tame," just one more product offered by the same record companies who were still getting Perry Como and Dean Martin on the charts. Once something that horrified our parent's generation for its raw, sensual energy, Rock and Roll's march to mainstream had turned it fun, clever, and almost innocent.Yes, the 1958 "Rock" hits included Chuck Berry's "Sweet Little Sixteen" and "Johnnie B. Goode," Jerry Lee Lewis' "Great Balls of Fire," and Buddy Holly's "Peggie Sue." But the "wild and crazy" rock hits were outnumbered by songs like the Coasters' "Yakity Yak," Danny and the Juniors' "At the Hop," and the Silhouettes' "Get a Job." The same year saw the growing market share of the "teen idols," such as Frankie Avalon and Ricky Nelson.

Before long "teen idols" like Fabian and "girl groups" like the Shirelles were also taking a share of the charts. And the Beach Boys, the most popular rock band of the early 1960s, eventually moved away from their "beach band" roots into more and more complex (but less dance-worthy) arrangements.

In contrast, emerging artists like Peter, Paul, and Mary, the Chad Mitchell Trio, Joan Baez, and countless others seemed to offer music that was fresh and authentic. It's probably no surprise that the Folk Revival movement (spoiler alert) grew right up to the beginning of the British Invasion, and began a long, but measurable downward slide soon after.

Though the Kingston Trio avoided blacklisting by staying out of politics, countless soloists and groups inspired by their success went back to Seeger and Guthrie for their inspiration and created the soundtrack for the Civil Rights movement and the early anti-Viet Nam war movement. In fact, long before Bob Dylan became the most prominent face of the "movement," he made a pilgrimage to Woody Guthrie's deathbed, during which he taught the young Arlo how to play "cross harp."

Expanding its Reach, Sort Of

As the Folk Revival movement grew, appreciation for musical traditions outside the Kingston Trio-centered mainstream grew as well. Traditional Blues musicians like Reverend Gary Davis, traditional Gospel musicians like the Clara Ward Singers, traditional Irish bands like the Irish Rovers, and many more were included in concerts. A number even found their way to emerging Folk record labels. Even Bluegrass got a nod - Pete Seeger defined it as "Folk music on overdrive" and printed the tablature of "Foggy Mountain Breakdown" in his banjo method book.That said (and Joan Baez, Buffy St. Marie, and Harry Belafonte notwithstanding), the vast majority of Folk Revival musicians who had long careers and multiple albums on mainstream labels were middle- or upper-class white people. So were most of the concert-goers and record buyers. So, though we were celebrating an apparent blurring of cultural lines, with, say, the sons of Klansmen sharing the stage with the grandsons of slaves, the Folk Revival moveoment never really changed American culture as we had hoped.

Today, if you buy a retrospective collection of "Folk" music, you'll mostly get a collection of songs by white people who were drawn to the music by their love of it, but you won't necessarily see "the whole picture" as we thought we saw it in the 1960s.

What was "Folk" and what was "Folk-Like"?

The Folk Revival movement included a flood of people who not only learned and passed on traditional songs, but who also wrote songs in traditional styles. A certain amount of this resulted from trying to make ancient texts and nearly-unsingable tunes more accessible to modern audiences. A certain amount resulted from copyright concerns - if I completely rewrote, then publicized an ancient song that no one else had ever heard of, shouldn't I get all the royalties from it? But mostly it just came from thousands of talented young people choosing to perform Folk-based music in Folk-based styles, and whose songwriting naturally fit into that stream.Nowadays, when someone sings a Tom Paxton song like "The Last Thing On My Mind," few people would have trouble classifying it as "Folk music," though it's not technically a "Folk song," by the strictest definition - we know who wrote it. But if I sing that song, or, say "City of New Orleans" in a "Folk concert" nobody is going to accuse me of being "inauthentic" or the like.

At the same time, there were many "outliers," groups that performed Folk-like material without necessarily being a deliberate part of the Folk tradition that Seeger and Guthrie and their disciples had nourished. Most outstanding, perhaps, were the New Christy Minstrels, a traveling musical theater troup that put on highly scripted and choreographed shows that imitated the folk jam sessions called Hootenannies. Though the Minstrels hit the charts with Folk-inspired songs like "Today" and "Green, Green," and included a few actual Folk songs in their shows, some of the more mainstream Folk artists had little use for them at the time. And this increased when the genre began trending more obviously political and the Minstrels did not follow suit.

At the same time, there were many "outliers," groups that performed Folk-like material without necessarily being a deliberate part of the Folk tradition that Seeger and Guthrie and their disciples had nourished. Most outstanding, perhaps, were the New Christy Minstrels, a traveling musical theater troup that put on highly scripted and choreographed shows that imitated the folk jam sessions called Hootenannies. Though the Minstrels hit the charts with Folk-inspired songs like "Today" and "Green, Green," and included a few actual Folk songs in their shows, some of the more mainstream Folk artists had little use for them at the time. And this increased when the genre began trending more obviously political and the Minstrels did not follow suit.

Don't get me wrong, Randy Sparks, their leader and songwriter, was a musical genius, working firmly within Folk Revival conventions. Many of the songs he wrote for the Minstrels could have been credibly performed by almost any group on the folk charts in that era.

And the Minstrels gave the Folk Revival a big boost, both in their hit records and their constant appearances. Many Folk fans' introduction to Folk-style music was through the Minstrels. And quite a few Minstrels alumni, including Barry McGuire and John Denver, went on to have independent Folk or Folk-influenced careers.

But the showmanship of the whole thing put some Folk music lovers off. I list the Minstrels in this section only because they're a frequent punching bag even today in some circles (and deliberately skewered in A Mighty Wind), but I could easily name several acts that were only "Folk" when the money was there. Unlike Randy Sparks and his Minstrels, who have kept touring decades after the "real money" stopped coming in.

The "who is really Folk" arguments continued well after the Folk Revival movement had passed from public consciousness. When - after over twenty years working in other genres - I began getting reacquainted with Folk music circles in the mid-1990s, I was surprised to hear that some of the "What is Folk" arguments were still going on. As someone once said about university politics - the fights are so vicious because the stakes are so small. Let's face it, thirty years after Folk music has lost its dominance on the radio, when only a small percentage of music-lovers even play or listen to traditional or Folk-inspired music, who really cares whether some Folk-inspired artist or song from a half-century ago was truly "authentic" or not?

The Rise of Folk-Rock

This history wouldn't be complete without describing the third generation of the Folk Revival, musically speaking. If the first generation consisted of the Weavers and their contemporaries, the second generation would consist of groups like Peter, Paul, and Mary who worked within and respected the Folk tradition to the point of constraining their writing and performances to traditional frameworks. Just after them came people like Paul Simon, James Taylor, and John Phillips who had - to some extent - cut their musical teeth during the Folk Revival movement and who remained heavily influenced by traditional styles even as they inched closer to mainstream popular music.Many traditionalists believe that Bob Dylan had sold out when he first played an electric guitar (albeit badly) at a Folk festival in 1965. But the truth is that Folk music has never been static, really. And, even more telling, its influence goes on.

Long after Folk music and even Folk Revival music ceased to be forces in the marketplace, many musicians continued to use Folk styles, idioms, and even instruments in their songs. The Folk influences on the Byrds, the Hollies, and Buffalo Springfield were unmistakable, but were even more obvious when three of their alumni, David Crosby, Graham Nash, and Stephen Stills, teamed up to form Crosby, Stills and Nash. Cat Stevens, after an early pop hit and a stay in a sanitarium, went acoustic and was often classified as "Folk" though he performed almost no traditional music and was never, technically, a part of the Folk Revival.

Even groups that adopted Rock band instrumentation like Poco and the Eagles kept elements of Folk Revival in their music, including traditionally-inspired harmonies and sometimes even banjos. Fortunately, for some folks who stayed firmly in the Folk idiom, this continuation of folk-like sounds on the radio allowed people like Richie Havens and Harry Chapin to still seem relevant years after Folk as a genre had fallen from public notice.

The list of Folk-Rock and Folk-influenced Rock artists would be too long to include. But it is hardly surprising today to hear a Folk "cover" group doing songs by Van Morrison, Neil Young, and countless others who mixed their pop hits with songs that were Folk in all but instrumentation.

Slip-Sliding Into Country

The earliest Folk Revival music and the earliest Country and Western music were very closely related. They began to diverge when Country and Western took on a life of its own, with mandatory cowboy hats and glitter-trimmed suits. That said, the chord choices and the melodic and harmonic traditions stayed virtually the same. For years, Johnny Cash would have folk singers on his television program, and they never had trouble jamming together. As the peak of the Folk Revival approached, though, political issues were driving the communities apart. Most Folk Revival musicians took the progressive side on issues like civil rights, and most Country musicians - closer to their roots in areas besides musical styles - stayed politically conservative. The gap widened as the sixties went on. The division wasn't universal, though. Earl Scruggs didn't see why Flatt & Scruggs couldn't expand their audience to include Folk-loving youth. In 1968, Flatt & Scruggs released an album with several Folk Revival songs, including "Blowin in the Wind" and "Where Have All the Flowers Gone." Personally, I played it to death, but the Folk fans as a whole were unimpressed. (Earl's desire to stay contemporary eventually contributed to the band's breakup, according to some sources.)

The division wasn't universal, though. Earl Scruggs didn't see why Flatt & Scruggs couldn't expand their audience to include Folk-loving youth. In 1968, Flatt & Scruggs released an album with several Folk Revival songs, including "Blowin in the Wind" and "Where Have All the Flowers Gone." Personally, I played it to death, but the Folk fans as a whole were unimpressed. (Earl's desire to stay contemporary eventually contributed to the band's breakup, according to some sources.)

A year later, when Bob Dylan made a point of recording with Country and Western musicians for his Nashville Skyline album, his fans saw it as a betrayal, maybe even one greater than bringing an electric guitar to the Newport Folk Festival.

A year later, when Bob Dylan made a point of recording with Country and Western musicians for his Nashville Skyline album, his fans saw it as a betrayal, maybe even one greater than bringing an electric guitar to the Newport Folk Festival.

Bridge-building went the other way, too. In the late 1960s, during the height of the Viet Nam war protests, the Smothers Brothers (a left-leaning comedy duo that worked within and lampooned Folk Revival conventions) promoted the career of Glenn Campbell, a died-in-the-wool Country singer whose breakout hit "Gentle on My Mind" was written by Folk Revival artist John Hartford.

Long after Folk Revival music was a dominant force in the music industry, there was still a "cross-pollination" of Folk Revival songs into C&W repertoires and vice versa. And by the mid 1980s, several names that I once knew as Folk Revival artists has made a place in C&W circles, without changing their songwriting style, or even their sound, if you discount the added steel guitars. Mary Chapin Carpenter, for one. There were others, but I think they're shy of being "outed."

In recent years, I have even heard Irish bands that are fans of American Folk Revival music mixing in Country songs that can be credibly performed in the same set. And I have known amateur Xers and Millenial Folk fans who assumed those same songs were Irish or at least Folk in origin. "Long Black Veil" for one. So the musical divide between Country and Folk has remained far smaller than the political divide.

Folk Gets Religion

You'll recall that during the early days of the Folk Revival, traditional Gospel singers were often welcomed onto the "Folk" stages. In addition, it was traditional for most Folk Revival acts to include at least one, if not many Gospel or Gospelish songs into their acts. (Noel Stookey's "Early in the Morning" being a prime example.)Though countless Northern Christians supported the Civil Rights movement, coinciding with the rise of the Folk Revival, later political tensions drew attention to the political schism between most folks who loved Folk Revival music (mostly progressive) and the televangelist-influenced right-wing churches. Let's just say that leading a Gospel sing-along at a Folk concert in 1971 was nowhere near as much fun as leading one in 1964. Gospel music may have divorced entirely from Folk-style music if it hadn't been for a rise of late-'60s counter-culture Christians (what the newspapers called "Jesus Freaks"), whose musical tastes and political views stayed the same even after their conversions.

It's probably hard to believe today, but the "Jesus Movement" of the late 1960s and early 1970s, used actual Folk and Folk-syle songs. Back in those days there was no "genre" of Christian music; there were young people trying to express their faith in the modes they knew best. If you went to a "Jesus Music" festival in the early 1970s, most or all of the acts would be acoustic-guitar-based.

In fact, one of the earliest Jesus Music fesivals - Icthus, in Wilmore, Kentucky - specified that "Folk music" with Christian themes must be used. The same festival later unplugged a Folk-style Christian artist who brought along an electric guitar player. Sound familiar?

Even Amy Grant's first big hits "El Shaddai" and "I Have Decided" were written by an accomplished acoustic guitarist - Michael Card - who writes and records Folk-style music with Christian themes to this day.

To me, much of what passes for "Contemporary Christian Music" on the radio today is just a shallow imitation of whatever pre-teen-oriented pop garbage is on the secular stations. But some of the better "worship music" composers still compose on guitar and write songs that are musically very similar to the Folk Revival songs of the early-to-mid 1060s.

I'm not saying that you'll find music in that genre to be particularly creative, only that the influence of Folk Revival conventions pervades to this day. (For more on the rise and fall of "Jesus Music" and related topics, check out my article A Brief History of Contemporary Christian Music.)

What About "Singer/Songwriters"?

Technically anyone who performs their own music publically is a "singer/songwriter." So most Folk Revival singers fit that category. But the term almost took on a genre-like quality in the 1980s and 1990s with individuals like Suzanne Vega, Bruce Cockburn. Generally, it refered to people who soloed, more or less acoustically, accompanying themselves on guitar or piano. As open mics and coffeehouses that featured live entertainment began spreading in that period, a lot of people called themselves "singer/songwriters" because there was no other acceptable name for what they were doing.That said, a great deal of what has passed for "singer/songwriter" music in the last thirty or so years shows significant Folk influence. And a number of people who would gladly have taken the title "Folk singer" back in the day when it was popular are calling themselves "singer/songwriters" today.

From about 1995 to 2005, I would use that moniker when trying to get gigs in places that wanted to seem trendy. Of course I had to watch my repertoire, or I'd slip into a sea chanty singalong or something and blow my cover. Nowadays, as I said, people aren't as afraid of the "F" word ("Folk") as they once were.

What about "Americana"?

Many people who perform traditional and Folk-inspired music today also have taken to calling themselves "Americana" because they still believe there is a stigma to the word "Folk." Technically, "Americana" includes Blues, Dixieland, Modern Jazz, Rockabilly, Minstrel, Bluegrass, Country, and the marches of John Phillip Sousa. If you play any of those genres, please call yourself accordingly. If you play three or more of them, "Americana" is probably a fine name for what you do.On the other hand, if you consider yourself a member of the Folk tradition that Guthrie, Seeger, and their disciples nourished, please consider calling it what it is. And play it well - you'll discover that the only stigma attached to the name is the stigma you give it if you perform it badly.

Across the Pond

This account wouldn't be complete without explaining one other side effect. In the earliest days of the Folk Revival movement, songs by people like Hudy Ledbetter ("Leadbelly") found their way to the UK and were adopted enthusiastically by British youth. This was the start of the mid-century Skiffle movement, which was somewhat analagous to the North American Folk Revival and actually fed us some good artists and songs. According to Billy Bragg, the movement was huge, wide-spread, grass-roots, and barely documented.Unfortunately, when the British record companies caught on that British youth were enjoying the home-made, visceral aspects of this new, and often rowdy acoustic-guitar-based music, they started trying to produce "Skiffle" records that would sound like the rest of what they produced. So the vast majority of vintage "Skiffle" music you can find online will make your skin crawl. You should know that it didn't sound like that when the Brit youths were banging it out on guitars on the street corners. I'm no expert on Skiffle, but I have a blog about why it was probably better than it sounds today here.

Here's an irony: soon after I wrote this article, I heard from a UK Folk fan who was complaining about a wave of "Americana" music there. Apparently, that term has become an umbrella for anyone wanting to play distinctively American music, especially "roots" music with Country and Western leanings. To at least one UK Folk fan, this is anathema. I withheld my observation that this kind of attraction to string bands and American roots music was exactly what started the Skiffle movement - because there are still some folks who are embarrassed by what Skiffle became in the hands of the UK record companies.

The last thing I'll say on that subject is that Paul McCartney, John Lennon, and George Harrison started playing Skiffle together before they went to Rock and Roll. So Folk Revival music influenced, not only most subsequent American forms of popular music, but British Rock as well. And that, in turn reinvigorated Rock and Roll in North America.

Folk music really is the gift that keeps on giving.

What Does "Folk Music" Mean Today?

To this day, when you say "Folk music" to a Baby Boomer, the first artist or group they think of is almost always whoever was on the charts when they first became fans of the genre. My father loved the Weavers and artists of that era, so when I think of "Folk music," I almost always think of Pete Seeger and the people who were in his circle. But my big sister was a fan of Peter, Paul, and Mary, so that group and other artists who performed similar music also come to mind, including the Chad Mitchell Trio, Gordon Lightfoot, the Limeliters, Judy Collins, and Buffy St. Marie, etc.

To other folks, "Folk music" started with the Kingston Trio; everyone previous was irrelevant; everyone subsequent to them was derivative. To others, Joan Baez or Bob Dylan are the quintessential example of Folk musicians, and everyone else is an also-ran.

So, fifty-odd years later, the folks who still consider themselves fans of Folk music are still at risk of dividing into camps, depending on whether Seeger, the Kingston Trio, Baez, or Dylan was dominating the charts during their "formative years." I discovered this in the 1980s, when I booked myself into a coffeehouse as a "Folk singer," and inadvertently disappointed a number of slightly older audience members who assumed I would know the entire Kingston Trio repertoire. (I don't, but if you mention the Chad Mitchell trio, say . . . . )

Nevertheless, the vast majority of Baby Boomers who were performers or even just serious fans of Folk or Folk Revival music in their youth do share some characteristics, and that's what I want to focus on.

Most of us:

- Love music that reflects the roots of traditional music forms.

- Would recognize about a thousand songs from that era, and be able to sing along with a pretty good portion.

- Have a natural sense of what kind of chord progressions fit and which don't (CSN good, Smashing Pumpkins bad).

- Have a natural sense of what kind of harmonies fit in and which don't (Carter Sisters good, Four Seasons bad).

- Have tried to learn guitar at some point in our lives.

- If asked to name our favorite pop or rock artists, would probably include Folk-influenced artists like James Taylor, Poco, or CSN.

- Find our love of Folk and Folk-inspired music ridiculed by people who know nothing about the Folk Revival except that it's not "cool" any more.

Regarding that last point, for a long time, my acquaintenances who were really Folk-singers by almost any definition have called themselves "singer/songwriters" or "Americana" because calling themselves "Folk" would have kept them out of venues where they would otherwise have been well-received.

Like the banjo, which became an object of ridicule by the late 1960s, but is enjoying a (small) revival of interest by Xers and Millenials, "Folk" music has been out of style so long that the term "Folk" doesn't have the negative connotations it had just a few years ago.

Maybe I'm just too old to care, but it seems to me that people respond differently to that label than they used to. Once there was a time when if I said I was a Folk singer, it would have been a "turn-off" to most people. ("Aunt Helen sang 'Michael, Row, the Boat Ashore' to me once, and if that's Folk music, you can have it.") Now the response is generaly neutral or even positive, like "Cool." Sometimes it's "Cool, what's that?" But it's still positive.

Conclusion

I'm not claiming that there's a Folk revival, or even a Folk Revival revival afoot, only that there are fewer barriers to actively seeking an interest, or even a career in Folk or Folk-influenced music than there were just ten years ago. But there are still a lot of misconceptions, and a whole generation of people who don't even know where to start when it comes to learning and learning about Folk music.So this will hopefully be the first of a series of articles that provide a sort of "introduction to Folk and Folk Revival" music to help people born a generation or two after the history I've been talking about catch up.

Whatever else you get out of our pages, I hope you enjoy your music and figure out how to make enjoyable music for those around you as well.

Whatever else you get out of our pages, I hope you enjoy your music and figure out how to make enjoyable music for those around you as well.

And please stay in touch!

- Paul

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

http://CreekDontRise.com

http://SchoolOfTheRock.com

http://classictrainsongs.com

All materials, illustrations, and content on this web page are copyrighted (c) 2016 by Paul D. Race. All rights reserved.

Creek Dont' Rise(tm) is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising

program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

For questions, comments, suggestions, trouble reports, etc. about this page or this site, please contact us.

| Visit our other pages: | |||||

| - Music - | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Trains and Hobbies - | |||||

|

|

|  |

|

|

| - Christmas Memories and Collectibles - | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Family Activities and Crafts - | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|