| Please Read: How to Help Our Site at No Cost to You - Some of our articles contain recommendations for products we like and vendors we personally trust. Some of those vendors may pay us a very small commission if you click on a link and buy their products. This costs you nothing at all and helps offset the costs of what we do. So if we point you to something you decide to buy later, please make certain you come back through our site and click on the link directly. Thanks. |

| This Site is a Cookie-Free Zone - Except for discussion forums that you have to expressly register for, none of our pages use cookies of any kind. Some of the vendors we link to do, but that won't affect you unless you click on a link to their pages. Your continued use of this page indicates that you agree to our policy. For details, click here. |

The Myth of "Parlor Guitars"

Sorry, but I have to say something. People are lying to you.

Okay, it's not a huge concern, and hardly affects anybody, but I hate deliberate misinformation, even about minor issues.

Countless internet music sites, web pages, newsletters, and even manufacturers are claiming that the guitars now being called "parlor guitars" are a late-19th or early-20th-century invention. According to the urban legend, people playing guitar somewhere between 100 and 140 years ago decided that "full-sized" guitars were too big and loud for playing in parlors and similar enclosed spaces. The story goes that manufacturers introduced small-bodied, deep-waisted guitars with 12-fret necks to "tame" the tone and size of the guitar.

Nothing could be further from the truth. These are the original "full-sized" guitars. Nobody shrank anything - they just look "shrunk" to people who grew up with much larger guitars.

Why It's Personal

I occasionally do historical reenactments. And as a musician who is also a lover of history, I always try to make certain the instruments I bring look like the instruments that would have been played in the time and place I'm representing. For example, when I play a 1910ish banjo player, I bring a banjo that is an exact visual match for the vintage instruments that have survived from that era. (Though it is louder and plays better, I confess.)

For example, when I play a 1910ish banjo player, I bring a banjo that is an exact visual match for the vintage instruments that have survived from that era. (Though it is louder and plays better, I confess.)

But I wouldn't dream of using the same banjo in, say, a Civil-War reenactment. I've seen far too many Civil War reenactors playing banjos with obvious improvements that weren't even invented until fifty to seventy years later. (See our article on "Civil War banjos" for more information.)

When I considered getting a guitar appropriate for 19th-century reenactments, I researched the kinds of guitars folks used back then. And I discovered that virtually all 19th-century guitars manufactured or played in North America look like what manufacturers are calling "parlor guitars" today.

The example to the right is a Washburn from the early 1900s. As you'll see further down, it is nearly identical to a C.F. Martin instrument built around 1845. The size, shape, and features of both reflect the vast majority of guitars made or played in the 1800s and many made and played before 1925.

The example to the right is a Washburn from the early 1900s. As you'll see further down, it is nearly identical to a C.F. Martin instrument built around 1845. The size, shape, and features of both reflect the vast majority of guitars made or played in the 1800s and many made and played before 1925.

Modern manufacturers and many guitar "experts" are claiming that this class of guitars is a "shrunk-down" version of "regular guitars" made specifically for playing in enclosed spaces indoors or - in a touch of misogyny - for women's dainty fingers. Completely obscuring the fact that these were the "regular guitars" from the earliest days of American guitar manufacturing.

The truth is these original "standard-sized" guitars look funny today because we're used to guitars that were considered oversized when they came out, but now are considered "normal."

But that's no excuse for a historical reenactor to drag a Jumbo, a Dreadnought, or even a "concert-sized" guitar into a cowboy, Civil War, or Victorian-era household setting.

Update for 2024 - Video Series - Though I'm keeping this article updated, and it has lots of details and supplementary information, the core information I present here is also presented in a video series that starts here

The Photo Record

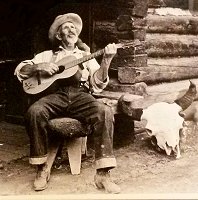

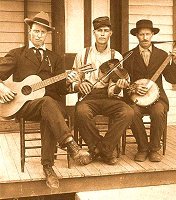

Just to put things into perspective, here is a range of photos dating from the 1860s and possibly as late as the 1920s (before there was widespread adoption of Jumbos, Dreadnoughts, and Loar-designed Gibson archtops). Clicking on each photo will bring up a larger version.When you're looking at those photos, see if they support the assertions that these guitars were designed for playing indoors or specifically by women.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In researching 19th-century guitars, I found countless other photographs of guitars roughly this shape and size, as well as 19th-century photographs and paintings of them being played by Civil War soldiers, cowboys and "nice ladies."

Interestingly enough in some old photos, the guitars seem larger than the guitars I'm writing about. You have to remember that people were generally smaller in those days, so, in some cases, the guitars look bigger in comparison than they would in a modern person's arms. But the narrow "waists" still distinguish them from the larger classes of guitars.

The Rise of Modern "Parlor" Guitars

If these guitars are based on designs that are a century and a half old, why did manufacturers determine that they needed to come up with a new name for them?Because countless acoustic guitar players were realizing that they were just plain easier to drag around and to play in casual settings, and even in arm-chairs, something that's pretty difficult with Jumbos and Dreadnoughts.

Moreover, many touring musicians realize that - with modern electronics - a well-made 19th-century-looking guitar sounds pretty much like a Jumbo or Dreadnought by the time the sound from the pickup works its way through the audio chain. So you see folks who use expensive custom Dreadnoughts in the studio touring with guitars that look - to the average non-musician - like toys. $800 toys, if you want the better versions, I'll grant you.

So how do manufacturers and their vendors explain the appearance of all these tiny-looking guitars? Calling them "standard-sized" just confuses people who think Dreadnoughts are "standard." So, in comic-book terms, you "retcon" them, inventing a new fictional origin story for the things. The marketeers now claim that somewhere just over a century ago, when people still had parlors, amateur guitar players demanded smaller instruments than they were used to for playing there. I'd be interested to know how they explain the appearance of these guitars well before the Civil War.

Here's a couple quotes:

"They were originally built for women's more compact frames, and they were named for their use as instruments intended to entertain guests in homes rich enough to include parlors."

"Parlor guitars [were] initially designed as small instruments for the wealthy as a way to entertain guests in their parlors."

"These were not only build [sic] for parlors but also for women, as with their smaller body it is easier to reach around the guitar without difficulty. This makes it ideal for women of that time and even today who are petite and have smaller fingers."

The downside of putting a new name on a very old and respected instrument? Nowadays any guitar that looks undersized compared to Jumbos and Dreadnoughts is labeled a "parlor guitar," even guitars that are nothing like their 19th-century predecessors, but are simply shrunk down for cost reasons or for children to learn on.

The Original Standard-Sized Guitars

Almost all guitars made before 1900 were the size of what are erroneously called "parlor guitars" today. Whether they were played in parlors, in concert halls, in saloons, on Civil War outposts, or around cattle drive campfires. In other words, what folks are calling "parlor guitars" today are the standard-sized guitars that everybody played before companies like Gibson and Martin began introducing larger instruments for use in loud string bands.The earliest guitars used in North America reflected the designs being played by Europeans of the time. It's easy to see their resemblances to 19-century Spanish guitars, but it might be worth noting that similar guitars were being made in Germany, too. (In fact, C.F. Martin came to the US from a guitar-making family in Germany, though he continually refined his designs once he arrived.)

The photo to the right shows a Martin guitar that was made about 1845. I can't tell without access to this instrument, but it's probably a "Size 1," Martin's most popular guitar for much of the 1800s. And before the Size 0 was invented in 1854 (below) it was the largest guitar Martin made. Many were smaller; in some cases, much smaller.

The photo to the right shows a Martin guitar that was made about 1845. I can't tell without access to this instrument, but it's probably a "Size 1," Martin's most popular guitar for much of the 1800s. And before the Size 0 was invented in 1854 (below) it was the largest guitar Martin made. Many were smaller; in some cases, much smaller.

The Tilton guitar to the right has an 1854 patent, though it might be newer by a decade or three. I tend toward the latter because it has adopted a metal tailpiece, typically an accommodation for players who preferred metal strings to gut.

The Tilton guitar to the right has an 1854 patent, though it might be newer by a decade or three. I tend toward the latter because it has adopted a metal tailpiece, typically an accommodation for players who preferred metal strings to gut.

You may also notice a slightly narrower upper bout. A number of examples are even narrower.

The undated C. Bruno guitar to the right is yet another example of a 'standard-sized' 19th-century guitar. Many guitars in this configuration were made well into the 1930s. The fact this this one has lost the slotted head may imply a post-1900 date.

The undated C. Bruno guitar to the right is yet another example of a 'standard-sized' 19th-century guitar. Many guitars in this configuration were made well into the 1930s. The fact this this one has lost the slotted head may imply a post-1900 date.

The guitars shown in the photos above, and countless others seem to follow the popular Martin "Size 1" in size and shape (there were many other manufacturers using similar designs, so it's impossible to tell from the photos if it's a Martin or some contemporary manufacturer copying Martin). For perspective, the Size 1 was 12.75" wide at the widest part, while a modern Dreadnought is 15 5/8" inches wide.

As mentioned earlier, nearly every photo from the mid-1800s to the 1900s show guitars with roughly the same size and shape. At any rate, it's nearly impossible to find a pre-1900 guitar photo or painting that shows a larger configuration, although a very few may be showing a Size 0, which was a little wider.

Which tells me that the oft-repeated story about guitars this size being "shrunk-down" versions that were invented to play "in the parlor" is, to put it nicely, hokum. These were the standard-sized guitars that were manufactured and played everywhere a guitar could be played well into the 20th century.

"Concert-Sized Guitars

The first "bump up" in size characterized guitars with wider bodies, was led by Martin's Size 0 guitars, first introduced in 1854, with bodies that were 13.5" wide at the widest part. Those were called "concert guitars," because their additional volume allowed them to be heard in larger settings like small concert halls.Size 0 is considered a sort of turning point in guitar history, and many folks define "Parlor" guitars as anything skinnier than a Size 0 (13.5" wide). Occasionally you'll see a guitar that is about the same size and shape as a 0 described as a Parlor guitar. That's a forgivable mistake, and if it otherwise fits the characteristics of a 19th century guitar could technically be used in reenactments from 1854 on. That said, Size 0s and 00s seem to have been vastly outnumbered by Size 1-format guitars for the remainder of the 19th century.

Size 0 was followed by Size 00, which seem to have first been sold commercially about 1873, though some older 00s have been found. They were called "Grand Concert" guitars and were 14 1/8" wide, still a little smaller than most modern classical guitars.

The Size 000 "Auditorium" guitar, which was 15" wide, was not introduced until 1902.

Did you ever wonder why "Concert," "Grand Concert" and "Auditorium" guitars have such grand names but seem so much smaller than most guitars folks are playing today? Because when those sizes were first mass-produced, they were considered massive. Little did folks know what was to come.

The chart below gives a general idea of the relative sizes and profiles of Martin's 19th-century guitars.

Based on photographs and examples of 19th-century guitars, the Size 1 seems to be the most popular and the most imitated of these instruments.

You'll also notice that as Martin expanded the line to include the larger 0, 00, and 000 guitars, they more-or-less moved the shape of the sides straight out, waist and all. That's one reason the relatively "narrow waists" of the Size 1 and similar guitars seems so distinctive today.

The "round shoulders" are typical of 19th-century guitars in general. When Martin lengthened the neck to 14 frets (starting in 1934), they mostly kept the guitars' overall size the same by squishing down the upper bout, which gives their modern guitars a more "square-shouldered" look.

Jumbos and Dreadnoughts

In the early 1900s, as string bands were overtaking the country, Gibson and Martin both experimented with even larger bodies. Gibson made flat-top "jumbos" and Loar-designed archtops, both of which became popular with Country musicians. Martin designed the relatively square-shouldered "dreadnought," which initially found a home in Bluegrass ensembles, and later became the "standard" for Folk-rock acoustic players.

To put these in perspective, the Martin Dreadnought was 15 5/8" wide and had a longer body than the 14-fret version of the 000. Jumbos tended to be around 16" wide.

Note: Part of the chart and many of the measurements in the above sections are from Onemanze.com's "Primer of C.F. Martin & Co. Model Names." I've checked them against other sources, and they seem to be "on target."

"Student" Guitars

If you look at the guitars played by most of the early Folk singers, you'll see that they are mostly "Concert-," "Grand Concert-," or "Auditorium"-sized. A few Folk singers did play guitars resembling Size 1, and a few chose Jumbos. By the 1970s, Dreadnoughts more-or-less became the standard for most surviving Folk and Folk-Rock performers.But as bigger and bigger guitars were adopted by professionals, mass-produced "student" guitars were being made in smaller sizes. This has led to folks trying to sell 1930s-to-modern cheapos as "parlor" guitars. And if you only look at the size of the things you might be fooled. But most of them are nothing like their predecessors in material or construction.

Most student guitars since the thirties abandoned slotted heads for solid heads (a cheaper solution). Virtually all of them used plywood tops. Brands like Kay and Harmony kept the metal tailpieces long after the name brand guitars had abandoned them.

As an example, the 1950s Kay student guitar at the right had a plywood top, a bolt-on neck, a fingerboard that was just an unpainted part of the neck, painted-on fret markers, and painted-on binding.

As an example, the 1950s Kay student guitar at the right had a plywood top, a bolt-on neck, a fingerboard that was just an unpainted part of the neck, painted-on fret markers, and painted-on binding.

Like most post-1950 student guitars, it also has squarer "shoulders" than 19th-century guitars, probably influenced by Martin's 14-fret models.

Surprisingly, the tiny minority of these that have survived and are playable have still developed some tone, but calling them "parlor guitars" ignores the fact that they have none of the better features of their nineteenth-century predecessors.

Eventually even student instruments migrated toward larger sizes, with only the cheapest lines retaining the smaller size. One result is that you see First Act's ukulele-sized child guitars listed as "parlor guitars"

"Singing Cowboy" Guitars

Trying to find more instances of 19th-century cowboy guitar players, I stumbled across an interesting mid-20th-century subset of "student guitars" that celebrates the movie and television version of the American West. No doubt this line takes its inspiration from the "singing cowboys," some of whom started out with authentic-looking Size 1-influenced guitars, but most of whom graduated to Jumbos.

No doubt this line takes its inspiration from the "singing cowboys," some of whom started out with authentic-looking Size 1-influenced guitars, but most of whom graduated to Jumbos.

The guitar to the right is apparently the same guitar as the Kay shown above, with the exception of a bolt-on bridge that made the metal tailpiece unnecessary, so there's room for Roy's signature.

I include this classification only because it's one you're likely to stumble on if you go looking for more photos of cowboys with guitars. Ironically, I have even seen guitars in this class listed as Parlor guitars, instead of student guitars that are far more notable for their stencil job than their sound or playability.

That said, this would look great displayed next to your Red Ryder BB gun and Mattel "Fanner Fifty" revolver and holster set.

"Parlor" Guitars for Historical Reenactments

For this part, I'm going back to my original focus - looking for guitars that would be suitable in a 19th-century reenactment - I'm thinking that the most convincing guitars would have the following characteristics.- Slotted peg head

- Round shoulders

- Narrow-looking waist, with a profile that resembles a Size 1 (most organizations wouldn't kick you out if you had a guitar with a 0 profile, and it is appropriate for any period after 1854.)

- 13.5" wide or narrower

- 12 frets between nut and body.

- For best sound unamplified, try to find a solid top.

Also, for a steel-string parlor, a metal tailpiece adds authenticity, but you won't find them on modern instruments. Just pretend you're playing "gut" strings and no one will notice.

Unfortunately, very few modern "Parlor" guitars have all of these characteristics, and those that do tend to cost a great deal. Because these models come and go, I won't get into too much detail about specific models.

19th-Century Influenced - As of January 2022, mass-produced guitars that could potentially stand in for 19th-century parlor guitars include:

- Size 1-ish

- The Ibanez PN1 series has a convincing Size 1 (or 2) shape and an attractive face, but a less-than convincing peg head and a relatively dull sound.

- The Luna Gypsy Parlor (made by Dean) has the same profile and similar issues, in addition to "new agey" markings that you might want to sand off when you're getting rid of that anachronistic glossy finish. It also has a 14-fret neck, which - to my knowledge - never appeared on a 19th-century guitar.

- The discontinued - and virtually impossible to find - Ibanez AVN3 maintained the Size 1 or 2 profile, but added a solid top and slotted head.

- Size 0-ish - A wealth of 0-inspired guitars are available, some of which have solid tops and slotted heads. They come and go, I'm afraid, so I won't hype any of them too much here, just providing a list worth looking into.

- The Ibanez PN 12 and PN15 lines are close to an 0 profile, though they still lack slotted heads or solid tops.

- The Ibanez AVN series "Parlor" guitars mostly seem to have solid tops, but most lack slotted heads (the apparently discontinued AVN5, AVN6, AVN9 and AVN10 series being exceptions). The ones I've seen have something like an 0 profile, so they'd pass in most circumstances.

- The Ibanez AC series has a solid top, but it seems to have a profile close to the 14-fret size 00, which would tend to push it into the 1900s.

- Alvarez AP66 and AP70 are in the 0 class, have slotted heads and solid tops. The glossy finish gives them away as 21s-century instruments, but that's not insurmountable. The AP66-ESHB has a dandy electric pickup, which would be handy if you're playing someplace where you need to look "old-timey," but also need to sound great through a PA.

- The discontinued Washburn WP11SENS had a solid cedar face and slotted head. A replacement of sorts, the Washburn WP33SRS-L has a solid spruce top, but - for some reason - a dark blue back and sides.

- The long discontinued R314KK looks very authentic, but many owners were disappointed with the laminated guitar's sound and physical construction. The Washburn R320SWRK has better reviews and a much steeper price. The

- The Breedlove Pursuit Parlor guitar has a solid face and slotted head.

- The Paul Reed Smith SE P20 is a great-sounding 0 lookalike, except for the distinctive PRS peghead which gives it away. (Recent customer reviews suggest there may be quality control issues that shouldn't arise at this price level, though.)

20th-Century-Influenced - Countless other instruments advertised as "Parlor" guitars are based on student guitar designs of the 1920s-1940s (such as the Kay and Roy Rogers guitars shown above). Sadly, the cheaper ones sound about like their plywood-topped predecessors did when they were brand new and had all the tone of a brick. (Sorry, but I grew up with the class of guitars that these are based on, so I have a right to "crack" on them.) In addition, inexpensive guitars are often shipped in desparate need of a setup, or even with fatal flaws built in - so if you order one be sure to have it checked out immediately.

That said, a few of these, in spite of low cost, have solid tops, so if you luck into a good one, or at least one that can be set up for playability, you may be very pleased.

Keeping in mind that many of the 0, 00, and 000 guitars lasted well into the 20th century, you can certainly use most of the list above if you're reenacting early 1900s. But signs that a guitar belongs firmly in the 20th century include: sunburst stain jobs, square shoulders, pick guards, and 14 frets between the nut and the body. Just sayin'. If your intent is to replicate a 1930s-1940s Delta Blues look, go for it, especially if you can find one with a solid top. But don't drag one to a Civil War reenactment.

Far worse are the countless $50-$100 "half-size" and "three-quarter-size" student guitars that are shaped like mini-classicals or mini-Dreadnoughts but advertised as "Parlor" guitars since that term became popular. Crappy student guitars are crappy student guitars whatever you call them.

Parlor Guitars as Starter Instruments?

Pros of Parlor Guitar as a Starter Instrument:

- Easier for smaller students to hold than dreadnought or jumbo guitars.

- If student is very young, the guitar can be equipped temporarily with nylon strings, then changed back to steel when the student is ready

- A parlor guitar takes up less space than a dreadnought or jumbo.

- If it is a nice instrument, the student can keep it indefinitely, even if a bigger guitar comes along eventually.

Cons of Parlor Guitar as a Starter Instrument:

- Given the same quality, a parlor guitar is not quite as loud as dreadnought or jumbo guitars.

- In some circles, a parlor guitar generally doesn't generally have the "cool" appeal as a dreadnought, so if peer pressure is an issue. . . .

I've come back to these descriptions, pros, and cons many times since I started this project, and the more I think about it, the more I think there's a lot to be said for starting younger students out on parlor guitars (not to be confused with the so-called "starter guitars" you can buy in supermarkets every Christmas season). If they can hold the thing properly, they can grow into it without outgrowing it.

Shopping?

Keeping in mind that many of the better modern parlor guitars are hard to find or even discontinued, we have put together a list of beginner-to-midrange parlor guitars that are widely available in the "Riverboat Music Parlor Guitar Buyers' Guide. (We set up Riverboat Music as a separate site to keep from cluttering up our reference pages, but any purchases made through that site help to support this page.)Conclusion

As I researched this article, I found myself including more and more content that didn't exactly align with my stated purpose, but might be of interest to anyone else researching these things. I also have a sort of confession. I have picked up several of the entry-level instruments with the intention of reviewing and making a video about them. Size 2 contenders included Ibanez' PN1NT, PN1MHNT, and AVN-3, as well as the Luna Gypsy mahogany Parlor. Size 0 contenders include two solid-topped Washburns (WP11SNS and WP33SRS-L). Plus some odds and ends.

I also have a sort of confession. I have picked up several of the entry-level instruments with the intention of reviewing and making a video about them. Size 2 contenders included Ibanez' PN1NT, PN1MHNT, and AVN-3, as well as the Luna Gypsy mahogany Parlor. Size 0 contenders include two solid-topped Washburns (WP11SNS and WP33SRS-L). Plus some odds and ends.

The Ibanez PN1s seemed to lack tone out of the box, but they got better as they "settled in." the Luna Gypsy size 2 sounded better and seemed to have a slightly better build, if you can overlook the anachronistic longer neck. The Ibanez AVN-3 (long unavailable) has a solid top and richer sound than the laminated guitars.

The Ibanez PN1s seemed to lack tone out of the box, but they got better as they "settled in." the Luna Gypsy size 2 sounded better and seemed to have a slightly better build, if you can overlook the anachronistic longer neck. The Ibanez AVN-3 (long unavailable) has a solid top and richer sound than the laminated guitars.

The Washburn WP11SNS and WP33SRS-L both have great sound for their size.

Keepers will probably include

- The Ibanez PN1MH or the Luna Gypsy Parlor for a beach guitar.

- The Ibanez AVN-3 for mid-1800s reenactments.

- The Washburn WP11SNS for 1870-1920 reenactments.

Best of luck to you all, and please let me know if you have any questions or corrections.

And please stay in touch!

All material, illustrations, and content of this web site is copyrighted ? 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006,

For questions, comments, suggestions, trouble reports, etc. about this page or this site, please

contact us.

And that, in turn, helps us provide more useful resources. Thank you!

Whatever else you get out of our pages, I hope you come away with some great ideas for "sharing the joy."

Whatever else you get out of our pages, I hope you come away with some great ideas for "sharing the joy."

2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024 by Paul D. Race. All rights reserved.

Creek Dont' Rise(tm) is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising

program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

How To Help Us Promote Traditional Music for Free: If you find our tips, explanations, and recommendations helpful when picking out a product, and you appreciate that we don't continually inconvenience you with irrelevant ads or obnoxious popups, Please Bookmark This Page and come back through it when you're ready to order. In some cases - not all - we get a very small portion of your purchase price, all of which goes to supporting our sites. Ironically, if you don't come through our page, someone else like Facebook or the Weather Channel will usually get that "fee" anyway. In the meantime, it costs you nothing. We never see who placed the order, so you don't have to worry about us pestering you with followup e-mails or some such. But it helps us know what pages our readers find useful, and it helps our advertisers know who to support.

| Visit related pages and affiliated sites: | |||||

| - Music - | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Trains and Hobbies - | |||||

|

|

|  |

|

|

| - Christmas Memories and Collectibles - | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Family Activities and Crafts - | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|